Nicole ColsterSpecial to BBC Mundo

BBC

BBCWhile Nicolas Maduro’s government lives on the brink under a military threat from US President Donald Trump, ordinary Venezuelans spend their time trying to figure out what to eat every day.

It’s Wednesday morning at Quinta Crespo, a popular market in downtown Caracas. Here, the potential escalation of the conflict is not the primary concern for Venezuelans, who follow the news while checking their wallets to find enough cash to pay.

“There will be no interference, nothing like that. What really bothers us is the rise in the dollar,” Alejandro Orellano tells BBC Mundo as he tastes coffee, waiting for customers who never seem to arrive.

In recent weeks, the Trump administration has deployed thousands of troops and military assets within striking distance of Venezuela, including the world’s largest warship. At least four international airlines canceled their flights to and from the country on Saturday, according to Reuters and Agence France-Presse, after a warning issued by US aviation authorities on Friday of “increasing military activity in or around Venezuela.”

It comes after a series of US air strikes against alleged drug boats in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific that left more than 80 people dead.

This is part of a broader effort that the administration says is necessary to stem the flow of drugs into the United States, but Maduro insists the threat is aimed at pushing him out of office.

Alejandro downplayed the importance of the speech between Washington and Caracas.

He has been selling vegetables in this market for five years. “Look, look how empty it is,” he said insistently, pointing to a long, lonely aisle filled with fresh fruits and vegetables.

A Christmas carol is playing, but the atmosphere is vaguely festive.

The common enemy of the people here: the sharp rise in food prices and the lack of purchasing power. This is partly due to the rapid decline in the value of the bolivar, which will lose 80% of its value this year, according to International Monetary Fund figures.

For example, a kilo of chicken costs about four times the official monthly minimum wage. Although the government provides bonuses to retirees and public sector workers, the funds are still insufficient to cover the basic food basket.

Consuelo, 74, doubts the possibility of an armed conflict with the United States and says that Venezuelans cannot store food in preparation for war.

“Let what happens happen! And that’s it!” She told the BBC, adding that worrying about the specter of war does not help much.

“Is it true? Is it false? It makes you sick, and you walk around stressed, it’s better to stay calm. Emotions can also affect your health,” continues this retired university professor who is still working.

“I didn’t do any panic buying, you need a lot of money to do that.”

Two economists living in Venezuela, who were consulted by the BBC for this report, preferred not to comment for fear of government retaliation.

Another expert, who requested anonymity, noted that “inflation has reached levels of about 20% per month.”

The International Monetary Fund expects a 548% increase in prices this year and says they will be worse in 2026, when they could rise to 629% – the highest figure on the continent.

Others see potential American intervention as an opportunity for regime change, but are afraid to talk about it publicly.

A trader from Ciudad Bolivar (in the southern state of Bolivar) told the BBC by phone: “We are afraid, silent, afraid that they will throw us in prison. I used to post things, but not anymore – I shouldn’t – because I don’t know who might turn me in.”

“There is hope and faith, but people are silent because of fear,” the woman says anonymously. “You don’t hear anyone talking about it; it’s just at home, with your family, but there is a hint of joy.”

Much of society is avoiding speaking publicly about issues that may be sensitive to Maduro’s government, after a wave of arrests following anti-government protests over disputed 2024 presidential elections, which were widely rejected by the international community.

The opposition and several countries, including the United States, rejected the result and recognized opposition candidate Edmundo Gonzalez as the legitimate president-elect.

Official figures show that after the elections, more than 2,000 people were arrested. At present, 884 people remain in prison for political reasons, according to the NGO Foro Penal.

“We’re all waiting for something to happen because it’s just and necessary,” says Barbara Marrero, a 40-year-old pastry chef. “We’ve been living in absolute misery for years.

“Venezuelans live day after day waiting for something to happen, but everyone is afraid [to speak] And no one says anything.”

Esther Guevara, 53 years old, who works in a medical laboratory, does not hide her concern amid tensions over the deployment of the US naval fleet.

“I’m worried because I don’t really know what’s going on – they might invade the area, or strike… People think it will be okay, but it’s dangerous,” she says. “A lot of innocent people could die.”

“I feel like something is cooking there, but I’m waiting,” she adds.

It is now midday.

It’s all business as usual along a busy street in eastern Caracas. Street vendors drive sales. Pedestrians come and go.

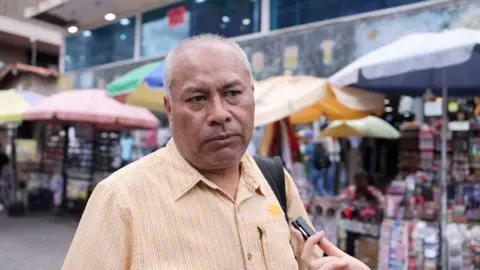

There’s Javier Jaramillo, 57, looking for items to resell at Christmas. He’s curious about the USS Gerald R. Ford, the aircraft carrier Washington transferred to the Caribbean.

He added, “I do not think this attack will happen. I think it is possible that there will be a dialogue, an agreement, or an agreement.”

However, he says that when there is a power outage, he thinks: “They come, they will come.”

Trump indicated he was open to diplomatic dialogue with Maduro, but also said he would not rule out military action.

Either way, Javier reiterates: “We are more worried about food. Venezuela is in bad shape. Inflation is eating us alive.”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/723a/live/572f0fe0-c6f3-11f0-a863-434ee92aa5e3.jpg

2025-11-23 00:02:00