Ayanda Charlie and Holly ColeBBC Eye Africa

BBC

BBCIn just under two weeks, leaders of some of the world’s major economies will gather in Johannesburg, South Africa’s economic heartland, for the G20 summit.

But just a few kilometers away from the stylish and very safe place is the city center that the authorities are struggling to improve and keep safe.

They face major challenges in cleaning up more than 100 abandoned buildings, many of which are plagued by rubbish and open sewage, some of which have been taken over by criminal gangs.

“There are weapons, there are drugs, there are prostitutes, everything is here,” said Nelson Khitani, a resident of the building known as MBV1, located in Joubert Park.

Neglect and lack of maintenance have stripped communal kitchens of their equipment, while excess human waste covers parts of what was once the laundry area.

Mr Khitani told BBC Africa Eye that rooms in MBV1 had been hijacked – a phenomenon where entire residential spaces or units are seized and controlled by criminals to collect rent for themselves and, in some circumstances, provide a base for illegal activities.

The BBC has identified and confirmed 102 abandoned or abandoned buildings in the inner city, an area of about 18 square kilometers (seven square miles), but other media reports have cited much higher numbers. Some of these places have been hijacked and are unfit for human habitation.

The state of the city was on President Cyril Ramaphosa’s mind when he spoke about the G20 summit to the city council in March.

“I found the city dirty,” he said.

“It’s a painful sight to walk through the city centre… You’ll find a number of abandoned buildings, buildings that have been hijacked, that don’t pay your fees and taxes.”

Johannesburg Mayor Dada Morero said at the time that the city was “ready to host the G20”.

Last month, as part of a “clean up” campaign across Johannesburg, the city council said the inner city had been “targeted… for the systematic removal of rampant disorder, illegal activities, stolen property and serious breaches of bylaws”.

But the challenges that await this global event are enormous.

The fire that broke out in one of these abandoned buildings, killing 76 people two years ago, was supposed to motivate people to act, but not much seems to have changed.

The BBC visited another building within the city, Fannin Court, where rooms were covered in dirt and littered with rubbish. A strong smell of human feces spreads through the building.

One resident, Sinthemba Makoma, told the BBC that the council-owned Fannin Court had been hijacked, and that the city council had cut off the water.

“The municipality was angry about the crime that happened in this building… that’s why they took it over [away] “Water,” said another resident, Sinkiwe Goodman Sithole.

The Johannesburg City Council did not respond to a BBC request for comment on the water supply at Fannin Court.

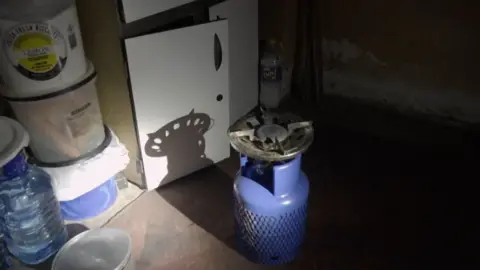

There is also no electricity supply, Mqoma said, adding that they use gas and solar lamps.

The lack of facilities means residents cook food using portable gas tanks to power stoves. But without water or fire extinguishers nearby, the fire risk is high.

Abandoned cars in the building’s basement were partially submerged in human waste that was overflowing into a nearby alley. Garbage was floating on top of slow-moving sewage sludge.

He showed the BBC a dark and unsanitary bathroom with a toilet, which he said he cleaned by pouring a bucket of water into it.

“When it flows [the toilet]“It goes downstairs,” he said.

The city’s housing problems are not a recent phenomenon.

Since apartheid and white minority rule ended in 1994, many black and mixed-race residents have moved from towns outside the city to the center to be closer to their workplaces.

This large influx of people has put severe pressure on the provision of adequate housing. Combined with a lack of investment and the departure of many wealthy owners, this has led to many buildings falling into disuse, with some becoming havens for illegal activity such as kidnapping.

Joseph, not his real name, is a former hijacker who spoke to the BBC on condition of anonymity. He said local criminals hired him to “clean up” a building and then “put up posters and write ‘apartment for rent’.” But collecting rent was not the main business.

“The main business in the building is cooking drugs,” he said. “They cook food elegantly. Many buildings, many of them here in Joburg, have been hijacked this way.”

Nyaope is a highly addictive street drug in South Africa, often containing substances such as low-grade heroin, cannabis, antiretroviral drugs, and in some cases even rat poison. It can cause abdominal pain, respiratory problems, and depression.

Joseph said he was haunted by those who may have suffered as a result of what happened where he worked.

He told the BBC: “Sometimes, when I’m asleep, I can see people, I see people. People died in these buildings. People went missing. I’m sorry for the wrong path in my life.”

Joseph said he left the gang because he discovered that other gang members were planning to kill him, adding that he was relieved to leave his life of crime.

But it gave insight into one possible reason authorities did not clear out the hijacked building: corruption.

Joseph claimed that evictions were prevented by “establishing a good relationship with… [the] City Council and the police,” which was “an issue [a] Cash bribe.

When asked about allegations of collusion with the building hijackers, City of Johannesburg deputy director of communications, Nthatisi Mudengwane, said the council had no “material” or “credible” reports to suggest that “any wrongdoing” had occurred.

When it came to cracking down on criminal activities in the hijacked buildings, the spokesman said there had been “operations where we found people in possession of drugs… [and] “Illegal weapons and these cases are currently before the South African Police Services for further investigation.”

Modingwane added that the council will “intensify” its operations to tackle criminal activity in the hijacked buildings and “make sure we clean up the city.”

Johannesburg police did not respond to a BBC request for comment on the bribery and intimidation.

Evacuating the residents of these abandoned and hijacked buildings seems to be the simple solution to the problem.

This could lead to much-needed redevelopment. But it would be an expensive and legally unclear exercise.

In the first place, the South African Constitution protects people’s right to housing.

This means that once a person is settled in a building and can prove that they have nowhere else to go, they cannot be forced out unless the state provides alternative housing.

This imposes a cost on the local authority, and moving people from the building is expensive in itself.

The mayor of Johannesburg Central, whose jurisdiction covers part of the inner city, said evictions could not be carried out on a larger scale or more frequently due to financial constraints.

Sheriff Marks Manjaba’s role is to carry out court orders, which includes handling evictions from premises once the property owner has obtained an eviction order.

Landlords – whether private or government – must pay for people’s relocation costs once they have obtained this order. But Mr Mangaba said large-scale evacuations were “a very expensive, multi-million rand operation”.

But even if the City of Johannesburg could afford to evict people in large numbers, it would create a mass homelessness crisis and the council would then have to provide housing.

Furthermore, South Africa’s Unlawful Eviction Prevention Act means that every eviction must come with a court order, meaning that attempts to move people can get stuck in the legal system.

Last March, the President highlighted the importance of transforming hijacked buildings in Johannesburg into “places of accommodation where our people can live a dignified life.”

But for many residents here, this vision remains hollow.

In the MBV1 building, Mr. Khatani said he had lived there since 2008 even though it was meant to be temporary accommodation.

He added that the city council informed him that there was no permanent residence “to go and put us in.”

“The city has no money and no one cares.”

More from BBC Eye Africa:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/1440/live/63dbdfe0-bb2a-11f0-920d-7f5aeca1e91c.jpg

2025-11-10 00:25:00