Suranjana TiwariBusiness correspondent in Asia

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen Prabowo Subianto campaigned to become Indonesia’s new president, he promised dynamic economic growth and major social change.

But his first year in office did not live up to this populist program. Instead, his ambitious pledges faced the realities of Southeast Asia’s largest economy.

In late August, a frustrated young man, worried about jobs, took to the streets to protest high costs of living, corruption and inequality – and the government was forced to revoke benefits for politicians, sparking public outrage. There were huge protests earlier in the year as well, against budget cuts that hurt spending on health care and education.

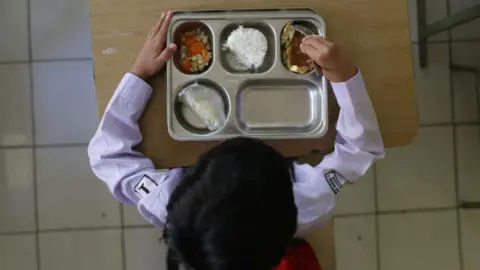

What didn’t help is that this coincided with an expensive free school meals program – at an annual cost of $28bn (£20.8bn). This program, which is the centerpiece of Prabowo’s agenda, aims to address child malnutrition, improve education outcomes and stimulate the economy. Officials describe it as “an investment in Indonesia’s future.”

However, in recent months pictures have emerged showing weak and dehydrated children – some as young as seven years old – hooked up to an intravenous drip. They were suffering from food poisoning after eating free lunches

With more than 9,000 children falling ill since the program was launched in January, critics question whether the program is achieving results at all, or whether it is draining public resources while racking up debt.

Analysts warn that all these challenges highlight broader issues in public spending and oversight – and these, in turn, point to deeper strains in Indonesia’s $1.4 trillion economy.

Discontent in the streets

It is a critical time for the vast archipelago of more than 280 million people, spread across thousands of islands.

Despite steady annual growth of about 5% in recent years, Indonesia is feeling pressure from slowing global demand, rising costs of living, and competition from regional neighbors such as Vietnam and Malaysia. Both countries have been successful in attracting foreign companies trying to diversify production away from China.

The protests that broke out in August, which left 10 people dead, showed the extent of public anger towards Prabowo’s government. The demonstrators accused her of prioritizing prestige policies and projects over providing economic support.

Prabowo – who has set an ambitious growth target of 8% by 2029 – and his ministers continue to defend their policies, saying they will create jobs and stimulate demand.

Indonesia’s Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs Airlangga Hartarto told the BBC: “We have experience of achieving growth above 7%. So… Indonesia knows that higher growth can be achieved. But of course, we have to see the global economy and global trade.”

Experts say achieving such growth will require careful management of public finances and foreign investment.

Adam Samdin of consultancy Oxford Economics said a new sovereign wealth fund, Dhanantara, targeting high-impact projects in renewable energy and advanced manufacturing, could spur higher growth.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAirlangga told the BBC that Indonesia was “ready” and willing to “spend in the right sector of the economy”.

But ambitious and challenging commitments such as the free school meals program make some question Prabowo’s priorities. Some health-focused NGOs are urging him to stop the scheme.

He defended this last month, saying: “It took Brazil 11 years to reach 47 million beneficiaries. We reached 30 million in 11 months. We are very proud of what we have achieved.”

Another example is India, which has the largest school lunch program in the world, feeding nearly 120 million students.

But unlike in Brazil and India, the Indonesian program has been accused of being ineffective, despite its much higher cost, due to mass cases of food poisoning.

Indonesia faces unique challenges. Samdin said it does not have the infrastructure needed to safely and quickly deliver meals to schools across its 6,000 inhabited islands.

This includes proper refrigeration transportation, as well as strict food safety standards and the resources needed to implement them to keep food fresh in the tropical heat.

The government therefore relies on third parties and contractors to implement the programme, making quality control more difficult.

But the faltering main program is not the only challenge facing Prabowo.

Search for investment

Indonesia has not been spared the trade war launched by US President Donald Trump, which now faces 19% tariffs on exports to America.

Airlangga, who participated in the negotiations, said he was grateful for the tariff rate that could compete with competitors such as Thailand, Malaysia and the Philippines, and that he expected the US-Indonesia trade deal to be signed by the end of October.

But 19% remains a high cost for exporters, who will also face pressure from redirecting Chinese goods to Asia to avoid high tariffs in Europe and the United States.

Indonesia – looking for new markets and partners – also signed a trade deal last month with the European Union, which it has been negotiating for nearly 10 years. Airlangga expects trade with the bloc to increase by two and a half times over the next five years.

But investment, which has stimulated industrialization and job creation in countries such as Thailand and Vietnam, is becoming a challenge here.

Foreign companies have long complained about the red tape and cost of doing business in Indonesia, but they still come in because of the large consumer base and resources. They are full of nickel and copper, which are integral to electric cars and other green technology, and palm oil.

But these were not industries that required massive manpower, meaning they did not create jobs on the same scale that the manufacturing sector did in countries like China and Vietnam.

Airlangga said Indonesia is now investing in the digital economy to create more job opportunities and boost growth. But whether it can provide enough people with the right skills to staff data centers and other similar projects is the big question.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesData centers also require investment, and investors are particularly upset after the sudden sacking of highly respected former Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati.

Mulyani’s home was ransacked during the protests by demonstrators, who blamed her for the high cost of living. She was succeeded by a relatively unknown official, Purbhaya Yudhi Sadiwa, who said the protests were due to financial “mistakes”.

He is a strong supporter of Prabowo’s ambition to achieve annual growth of 8% by 2029, a rate that the country has not achieved since the 1990s.

Even the current expansion rate of 5% is disputed by some economists, who also say economic data has been politicized to achieve Prabowo’s growth target. Erlangga denied this.

“I am optimistic that Indonesia remains attractive,” he said, citing “the value chain, investment climate and President Prabowo’s speed in deregulating.”

However, economists say falling auto sales, shrinking foreign investment, shrinking manufacturing and reports of layoffs suggest that economic activity is weakening, rather than strengthening.

“The Indonesian economy is consumption-driven, so from that point of view it can continue to provide a steady driver even if it does not grow significantly,” Samdin said.

“Growth may slow, but the sheer size of the population will provide some economic activity.”

This may reassure optimistic investors, but it does not solve the challenges that await President Prabowo.

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/6ccc/live/b0db3bb0-ab26-11f0-a94b-bd0a0d9557d9.jpg

2025-10-19 22:54:00