justin rowlatt,Climate Editor and

matt mcgrath,Environment correspondent

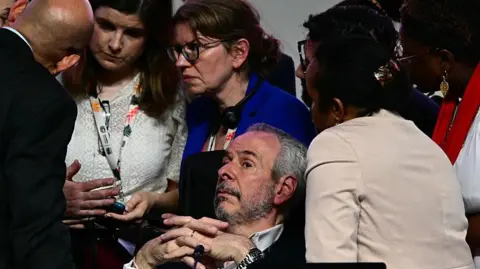

Getty

GettyWithin three decades of these meetings, aimed at forging a global consensus on how to prevent and deal with global warming, they would become among the most divisive.

Many countries were angry when the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30) concluded in Belem, Brazil, on Saturday without mentioning fossil fuels that have been warming the atmosphere. Other countries – especially those with the greatest gains from their continued production – felt vindicated.

The summit was a reality check of the extent to which the global consensus on what to do about climate change has collapsed.

Here are five key points from what some have called “the truth police.”

Brazil – not their finest hour

The most important outcome of COP30 is that the climate “ship” is still afloat

But many participants are unhappy because they didn’t get anything close to what they wanted.

Despite the warmth felt by Brazil and President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, there is frustration with the way they conducted this meeting.

From the beginning there appeared to be a gap between what President Lula wanted this meeting to achieve, and what the President of the COP, President Andre Correa do Lago, felt was possible.

So Lula spoke about the roadmap away from fossil fuels to a handful of world leaders who came to Belém before the official start of the COP.

The idea was embraced by a number of countries including the UK, and within days there was a campaign to formally introduce this roadmap into the negotiations.

Do Lago wasn’t keen. His North Star was unanimous. He knew that forcing the fossil fuel issue onto the agenda would tear it apart.

Although the initial text of the agreement contained some vague references to things that seemed like a roadmap, they disappeared within days, never to return.

Colombia, the European Union and about 80 countries have tried to find language to indicate a stronger move away from coal, oil and gas.

In order to reach consensus, do Lago held a group meeting, a type of Brazilian group discussion.

He made things worse.

Negotiators from Arab countries refused to join those who want a path away from fossil energy.

The European Union did not receive much attention from major producers.

The Saudi delegate told them in a closed meeting, according to one observer: “We make energy policy in our capital, not in your capital.”

Oh!

There was nothing that could bridge the gap, and the talks teetered on the brink of collapse.

Brazil has come up with a face-saving idea of roadmaps on deforestation and fossil fuels that could be developed outside the COP.

They have been warmly welcomed in the public halls – but their legal status is uncertain.

Tom Ingham/BBC

Tom Ingham/BBCThe EU had a bad COP

They are the richest group of countries still in Paris Agreement But this COP was not the best of times for the EU.

While they made a big deal about the need for a fossil fuel roadmap, they got themselves into a bind over another aspect of the agreement that they ultimately couldn’t get out of.

The idea of tripling funds for climate adaptation was present in the early text and continued into the final draft.

The wording was so vague that the European Union did not object – but more importantly, the word “triple” remained in the text.

So when the EU tried to pressure the developing world to support the idea of a fossil fuel roadmap, it had nothing to sweeten the deal – since the concept of tripling the volume of fossil fuels had already been established.

“Overall, we are seeing an EU under siege,” said Li Xu of the Asia Society, a long-time observer of climate politics.

“This partly reflects the real-world power shift, the emerging power of the Bezeq and BRICS countries, and the decline of the European Union.

The EU was furious, but apart from tripling funding from 2030 to 2035, it had to go ahead with the deal, achieving very little on the fossil fuel front.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe future of the COP is in question

The most pressing question asked here at COP30 over the two weeks was about the future of the “process” itself.

Two positions are often heard:

How ridiculous would it be to fly thousands of people halfway around the world to sit in giant air-conditioned tents to debate commas and convoluted word interpretations?

How ironic is it that the main discussions here, about the future of how we will power our world, are happening at three in the morning among sleep-deprived delegates who haven’t been home for weeks?

The idea of a COP has served the world well in eventually achieving the Paris climate agreement – but that was a decade ago, and many participants feel it no longer has a clear and powerful purpose.

“We can’t get rid of it completely,” Harjit Singh, an activist with the Fossil Fuel Treaty Initiative, told BBC News.

“But it will require retrofitting. We will need operations outside of this system to help complement what we have done so far.”

Energy costs and valid questions about how countries will reach net-zero emissions have never been more relevant – and yet the idea of a COP seems so far removed from the daily lives of billions of people.

It is a consensus process that comes from a different era. We are not in this world anymore.

Brazil has recognized some of these issues and has tried to make this an “implementation condition” and has focused a lot on the “energy agenda.” But no one really knows what these ideas actually mean.

The COP leaders are reading the room – they are trying to find a new approach that is needed or else this conference will lose all relevance.

Trade comes from the cold

For the first time, global trade became one of the main issues in these talks. There have been a “concerted” effort to raise the issue in every negotiating room, according to veteran COP observer Alden Meyer of climate think tank E3G.

“What does this have to do with climate change?” Maybe you’re thinking.

The answer is that the EU is planning to impose a border tax on some high-carbon products such as steel, fertilisers, cement and aluminium, and many of its trading partners – most notably China, India and Saudi Arabia – are unhappy with this tax.

They say it is unfair for a large trading bloc to impose what they call a unilateral measure – “unilateral” is the technical term – such a measure because it will make the goods they sell in Europe more expensive – and therefore less competitive.

The Europeans say this is not true because this measure is not about stifling trade, but about reducing greenhouse gases – and tackling climate change. They already charge producers of these products for the emissions they produce and say the border tax is a way to protect them from less environmentally friendly but cheaper imports from abroad.

They say, if you don’t want to pay our border tax, just impose emissions fees on your polluting industries – collect the money yourself.

Economists love this idea because the more expensive pollution is, the more likely we will all switch to clean energy alternatives. Although – of course – it also means that we will pay more for any goods we buy that contain contaminated materials.

This issue was resolved here in Brazil through a classic COP settlement – pushing the discussions into future talks. The final agreement launched an ongoing dialogue on trade in future UN climate talks, which includes governments as well as other actors such as the World Trade Organization.

Tom Ingham/BBC

Tom Ingham/BBCTrump wins by staying away, and China wins by staying calm

The world’s two largest carbon emitters, China and the United States, had similar impacts on this COP, but they achieved these impacts in different ways.

US President Donald Trump stayed away, but his position encouraged his allies here.

Russia, usually a relatively quiet participant, has been at the forefront in obstructing efforts to draw up road maps. While Saudi Arabia and other major oil producers have been predictably hostile to curbing fossil fuels, China has remained calm and focused on making deals.

Ultimately, experts say, China’s actions will outpace the United States and its efforts to sell fossil fuels.

“China has maintained a low political profile,” says Li Xu of the Asia Society.

“And focus on making money in the real world.”

“Solar energy is the cheapest source of energy, and the long-term trend is very clear. China dominates this sector and this puts the United States in a very difficult position.”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/5754/live/fb183cf0-c7f5-11f0-975d-d5fa2587428e.jpg

2025-11-23 00:10:00