BBC World Service

Adel Amin Akon

Adel Amin AkonIn the quiet and narrow corridors of Srinagar in the Indian Kashmir, a small, lightly lit workshop stands as one of the last crafts that fades.

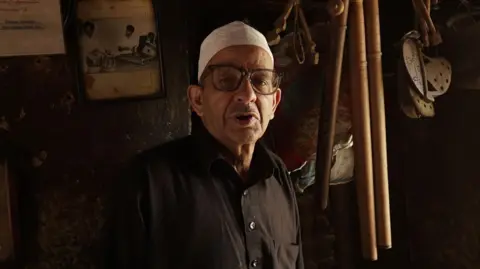

Inside the store, Ghulam Mohamed Zaz, who is widely believed to be the last craftsman in the area can make a Santor by hand.

Santoor is a semi -semi -semi -semi -semi -perverted musical instrument, similar to Dulcimer, which is played with a hammer. It is known for its color similar to the crystal bell, and it was the signature of Kashmir music for centuries.

Mr. Ghulam Muhammad belongs to proportions of craftsmen who built chain machines in Kashmir for more than seven generations. The name of the Zaz family has always been synonymous as Santor, Rabb, Saranji and Wasitar.

But in recent years, the demand for handmade tools has diminished, and it is replaced by versions made of the device cheaper and faster in production. At the same time, music tastes have changed, in addition to the decline.

“With hip -hop music, rap, and e -music that now dominates the Kashmir audio tape, young generations are no longer connected to the depth or discipline of traditional music,” says Shapir Ahmed Mir, a music teacher. As a result, the demand for Santoor collapsed, leaving the craftsmen without trainees or a sustainable market.

Adel Amin Akon

Adel Amin AkonIn his century -old store, Mr. Ghulam Mohamed sits next to a hollow bloc of wood and worn iron tools – quiet residue for traditions fading.

“No one is left [to continue the craft]”He says.” I am the last.

But it was not always that way.

Over the years, the Sufi artists and folk artists played by Mr. Ghulam Muhammad played manually.

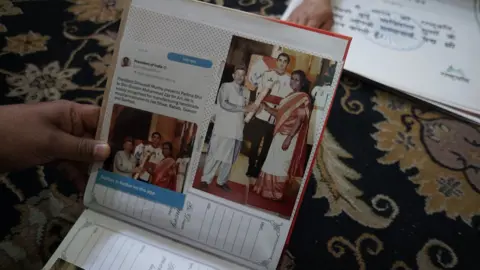

A picture in his store is Maestros Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma and Bhajan Sopori with his tools.

It is believed that he grew up in Persia, Sanor arrived from India in the thirteenth or fourteenth century, and spread across Central Asia and the Middle East. In Kashmir, it took a distinctive identity, becoming a centrality of Sufi hair and folk traditions.

“Originally part of Suffiana Mausiqi (the tradition of band’s music), Santoor had a soft, popular tone,” says Mr. Mir.

Bandit Chef Kumar Sharma later says with her classic Indian music, by adding chains, redesigning bridges for the wealthiest resonance and introducing new operating technologies.

Mr. Mir, who deepens in his scope, adds that Bahjan Soburi, who has the roots of Kashmiri, “the depths of its color and its flooding with Sufi expression”, and helps to consolidate the place of Sanor in Indian classic music.

Another picture shows Mr. Ghulam Mohamed, receiving Badma, a Shrew from President Dropadi Mirmo in 2022, was honored for his literal program with the fourth highest civilian award in India.

Gety pictures

Gety picturesMr. Ghulam Muhammad was born in the 1940s in Zina Caadal, a neighborhood named after a creative bridge that served as a lifeline for trade and culture in Kashmir. He grows up, he was surrounded by his family’s voices and tools.

Health issues forced him to leave official education at an early age, when he started learning the art of Santor’s manufacture from his father and grandfather – both of them as a master.

“They taught me not only how to make a tool but how to listen – to wood, air and hands that you will play,” he said.

He says: “My scenes are used to calling the courts of local kings and are often required to build tools that can calm hearts,” he says.

In its workshop, a wooden seat lined with chisels and chains beside the incomplete structural frame. The smell of air is dimmed from the elderly walnut wood, but there is no mechanism on the horizon.

Mr. Ghulam Mohamed believes that the machine making tools lack the warmth and depth of those who were designed by hand and that sound quality does not come close to anywhere.

Al -Harfi says that making Santor is a slow and deliberate process. It begins to choose right wood, aged between at least five years. Then the body is carved and sprayed for the optimal resonance, and each of the 25 bridges are placed accurately and placed.

More than 100 chains are added, followed by the strenuous control process, which may take weeks or even months.

He says, “It is a craft of patience and perseverance.”

Gety pictures

Gety picturesIn recent years, social media influencers have visited the workshop of Mr. Ghulam Mohamed, where they shared her story online. He appreciates attention, but he says that he did not lead to real efforts to preserve or inherit the craft.

He says: “These are good people, but what will be in this place when I go?”

With the presence of his three daughters who follow other professions, no one in the family to continue his work. Over the years, he had offers – government grants, promises to the trainees, and even suggestions from the Ministry of Handicrafts for the State.

But Mr. Ghulam Muhammad says that he is “not looking for fame or charity.” What he really wants is someone to move art forward.

Now in his eighties, he often spends hours next to Santor, and listens to silence that has not yet been completed.

“This is not just wooden works,” he says.

“It is poetry. Language. A tongue gives it to the tool.

“I hear Sanur before he plays. This is the secret. That’s what should be passed,” he added.

As the outside world embraces modernity, the workshop of Mr. Ghulam Muhammad remains not touched by time – slow, silent and full of the smell of walnuts and memory.

He says: “Wood and music, both of them die if they do not give them time.”

“I want someone who really loves the craft to take forward. Not for money, not for cameras, but for music.”

Follow BBC News India Instagramand YouTube, twitter and Facebook.

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/9305/live/23dec680-6230-11f0-8bb8-6da7e50368a3.jpg

2025-07-27 01:04:00